Climate change is often discussed within national contexts—countries set targets, report emissions, and implement adaptation strategies within their own borders. Yet the atmosphere, oceans, rivers, ecosystems, and weather systems that drive climate impacts do not recognize political boundaries. Transboundary climate change refers to climate-related causes, impacts, and responses that cross national borders, linking the actions and vulnerabilities of one country to those of others. From air pollution drifting across continents to rivers shared by multiple states facing climate-induced floods or droughts, transboundary climate change highlights the deeply interconnected nature of our planet.

Understanding transboundary climate change is essential for effective global climate governance. No country, regardless of its wealth or emissions profile, can fully insulate itself from climate impacts generated elsewhere. This blog post provides a comprehensive explanation of transboundary climate change, exploring its drivers, key pathways, real-world examples, governance challenges, and opportunities for cooperation. By the end, it should be clear why addressing climate change requires not only national action but also robust regional and international collaboration.

DEFINING TRANSBOUNDARY CLIMATE CHANGE

Transboundary climate change can be understood in two closely related ways:

Transboundary causes: Greenhouse gas emissions and land-use changes in one country contribute to global climate change, affecting climate systems worldwide.

Transboundary impacts: The physical, ecological, social, and economic impacts of climate change cross borders, affecting neighboring or even distant countries.

Unlike localized environmental problems, climate change operates through global systems such as the atmosphere and oceans. Carbon dioxide emitted from a power plant in one country mixes evenly in the global atmosphere, influencing temperature, precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events elsewhere. Similarly, climate impacts such as sea-level rise, shifting fish stocks, or regional droughts often spill over political boundaries, creating shared risks and responsibilities.

Transboundary climate change also includes policy and economic spillovers, where climate policies in one country affect trade, investment, migration, and development pathways in others. For example, carbon border adjustment mechanisms or climate-driven migration flows have clear transboundary dimensions.

THE SCIENTIFIC BASIS: WHY CLIMATE CHANGE IS INHERENTLY TRANSBOUNDARY

- The Global atmosphere

The atmosphere is a single, interconnected system. Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide disperse globally within months to years. This means that the location of emissions matters far less than their total volume. Climate change is therefore a cumulative, global problem driven by aggregate emissions over time.

- Ocean circulation and heat transport

Oceans absorb more than 90% of the excess heat caused by greenhouse gas emissions and transport it across the globe through complex circulation systems. Changes in ocean temperature and currents can alter weather patterns, fisheries productivity, and sea levels in regions far from the original source of emissions.

- Hydrological and ecological connectivity

River basins, mountain ranges, forests, and ecosystems frequently span multiple countries. Climate-induced changes in rainfall, glacier melt, or ecosystem health in one part of a shared system can have cascading impacts downstream or across borders. For example, reduced rainfall in an upstream country can intensify water scarcity in downstream nations.

These scientific realities make climate change fundamentally transboundary, requiring cooperative approaches grounded in shared understanding and trust.

MAJOR PATHWAYS OF TRANSBOUNDARY CLIMATE IMPACTS

1. Shared water resources

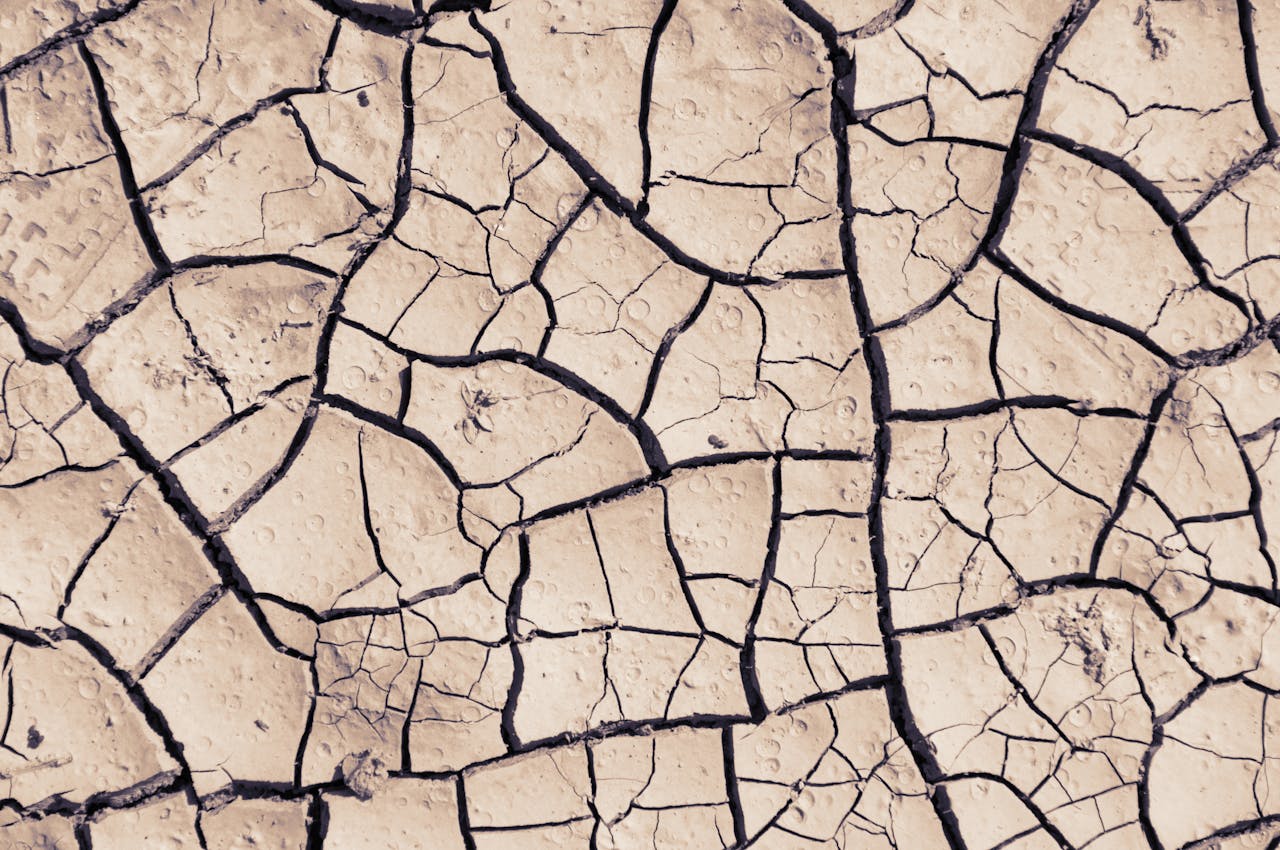

More than 260 river basins and countless aquifers are shared by two or more countries. Climate change affects these shared water systems through altered rainfall patterns, increased evaporation, glacier retreat, and more frequent extreme events such as floods and droughts.

In transboundary river basins, climate change can intensify existing tensions over water allocation, infrastructure development, and ecosystem protection. At the same time, it can also create opportunities for cooperation, such as joint early warning systems, data sharing, and coordinated water management.

2. Air Pollution and atmospheric transport

While climate change is distinct from air pollution, the two are closely linked. Many sources of greenhouse gases also emit air pollutants such as black carbon and ozone precursors. These pollutants can travel long distances across borders, affecting air quality, human health, and regional climate patterns.

For instance, black carbon emissions from one country can accelerate glacier melt in neighboring regions by darkening snow and ice surfaces. This demonstrates how local emissions can have regional climate consequences.

3. Ecosystems and biodiversity

Climate change is driving shifts in species distributions, migration patterns, and ecosystem boundaries. Many species cross national borders as they move in response to changing temperatures and precipitation. Marine ecosystems are particularly transboundary, with fish stocks migrating across exclusive economic zones as ocean temperatures change.

These shifts can disrupt livelihoods, food security, and conservation efforts, requiring coordinated management across borders to avoid conflict and overexploitation.

4. Extreme weather events

Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as heatwaves, storms, floods, and droughts. These events often have cross-border impacts, especially in regions with shared weather systems or interconnected infrastructure.

A severe drought in one country can reduce agricultural output, drive up food prices, and affect food security in neighboring states. Similarly, storms and floods can damage regional supply chains and energy networks.

5. Human mobility and security

Climate change acts as a risk multiplier, exacerbating existing social, economic, and political stresses. Climate-related impacts such as sea-level rise, drought, and extreme heat can contribute to displacement and migration, often across borders.

While climate change is rarely the sole cause of migration, it can intensify pressures that lead people to move in search of safety and livelihoods. Managing climate-related mobility is therefore a key transboundary challenge with humanitarian, economic, and security dimensions.

ECONOMIC AND POLICY SPILLOVERS

- Trade and Supply Chains

Modern economies are deeply interconnected through global supply chains. Climate impacts in one region—such as floods disrupting manufacturing hubs or droughts affecting agricultural production—can reverberate through international markets.

Climate policies can also have transboundary economic effects. For example, the introduction of carbon pricing or environmental standards in one country can influence production costs, competitiveness, and trade flows in others. These dynamics underscore the importance of aligning climate policies to avoid unintended consequences and promote fair outcomes.

- Carbon leakage and border measures

Differences in climate ambition between countries can lead to concerns about carbon leakage, where emissions-intensive activities shift to jurisdictions with weaker regulations. In response, some countries are considering or implementing carbon border adjustment mechanisms.

While such measures aim to protect climate integrity, they raise complex transboundary issues related to trade, equity, and international cooperation, particularly for developing countries.

- Equity and responsibility in a transboundary context

Transboundary climate change raises fundamental questions of equity and responsibility. Countries differ widely in their historical contributions to greenhouse gas emissions, their current emissions levels, and their capacity to respond to climate impacts.

Many of the countries most vulnerable to transboundary climate impacts—such as small island developing states or least developed countries—have contributed least to the problem. Yet they often face the most severe consequences, including sea-level rise, extreme weather, and economic disruption.

Addressing transboundary climate change therefore requires principles of fairness, common but differentiated responsibilities, and support for vulnerable countries through finance, technology transfer, and capacity building.

GOVERNANCE CHALLENGES

- Fragmented institutions

Climate change governance is spread across multiple levels and institutions, from local authorities to international agreements. Transboundary impacts often fall through the cracks between national mandates and sectoral responsibilities.

For example, a river basin authority may focus on water management without fully integrating climate projections, while climate policies may not adequately consider transboundary water implications.

- Data and information gaps

Effective transboundary cooperation depends on shared data, common methodologies, and mutual trust. Yet many regions lack reliable climate data, monitoring systems, or mechanisms for data sharing across borders.

- Political tensions and trust deficits

Historical conflicts, power asymmetries, and competing development priorities can hinder transboundary climate cooperation. Climate change can exacerbate existing tensions, particularly in regions with contested resources or fragile governance.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR COOPERATION

Despite these challenges, transboundary climate change also offers opportunities for collaboration and mutual benefit.

- Regional cooperation frameworks

Regional organizations and agreements can provide platforms for coordinated climate action, including joint adaptation planning, shared infrastructure investments, and harmonized policies.

- Integrated resource management

Approaches such as integrated water resources management or ecosystem-based adaptation can help countries manage shared resources more sustainably under changing climate conditions.

- Climate diplomacy and peacebuilding

Climate cooperation can serve as a confidence-building measure, fostering dialogue and trust between countries. Joint efforts to address shared climate risks can contribute to broader peace and stability.

- Finance and technology sharing

International climate finance and technology cooperation can help bridge capacity gaps and support collective action. Transboundary projects, such as regional renewable energy grids or early warning systems, can deliver significant co-benefits.

CASE STUDIES OF TRANSBOUNDARY CLIMATE CHANGE

While a detailed exploration of specific regions is beyond the scope of this post, examples from shared river basins, regional seas, and cross-border ecosystems around the world illustrate the realities of transboundary climate change. These cases show both the risks of uncoordinated action and the benefits of cooperation.

THE ROLE OF INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS

Global agreements such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement provide overarching frameworks for addressing climate change. While these agreements focus primarily on national commitments, they also encourage cooperation, information sharing, and support for vulnerable countries.

Other international legal instruments related to water, biodiversity, trade, and human rights also play important roles in addressing transboundary climate issues. Aligning these frameworks remains an ongoing challenge and opportunity.

LOOKING AHEAD: BUILDING RESILIENCE BEYOND BORDERS

As climate impacts intensify, the importance of transboundary approaches will only grow. Future climate governance must better reflect the interconnected nature of climate risks and responses.

Key priorities include:

- Strengthening regional and cross-border institutions

- Integrating climate science into transboundary resource management

- Enhancing data sharing and early warning systems

- Addressing equity and capacity gaps

- Fostering inclusive, participatory approaches

By viewing climate change through a transboundary lens, policymakers, practitioners, and communities can develop more effective, equitable, and resilient responses.

CONCLUSION

Transboundary climate change underscores a fundamental truth: climate change is a shared challenge that transcends borders, sectors, and generations. The causes of climate change are global, its impacts are interconnected, and its solutions require cooperation at all levels.

Recognizing and addressing the transboundary dimensions of climate change is not optional—it is essential for sustainable development, regional stability, and global resilience. By embracing collaboration, fairness, and shared responsibility, the international community can turn the challenge of transboundary climate change into an opportunity for collective action and a more resilient future for all.